I’ve been a bit behind on blogging in general, but made five posts in the Algorithmic Pattern blog yesterday.. On … More

Category: papers

My publications list – updated

My publications list was missing some entries and many of the PDFs. I started uploading everything to Zenodo, but although … More

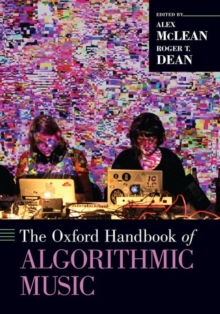

Oxford Handbook of Algorithmic Music in paperback

The Oxford Handbook of Algorithmic Music (I always have to check whether it’s of or on) is out in paperback … More

NIME – algorithmic pattern

I gave a paper and performance for the New Interfaces for Musical Expression conferece last week. It was to be … More

Digital Art: A Long History and Feedforward

I wrote a paper with Ellen Harlizius-Klück and Dave Griffiths called “Digital Art: A Long History“, accepted to Live Interfaces … More

Oxford Handbook of Algorithmic Music

It’s out! It took a little bit longer than planned, but hugely happy to have the Oxford Handbook of Algorithmic … More

Oxford Handbook on Algorithmic Music – draft ToC

Part of the reason I might have been a bit slow the past year or so – the draft table … More

2nd Workshop on Philosophy of Human+Computer Music

Happy to have the following abstract accepted for the 2nd Workshop on Philosophy of Human+Computer Music, in the University of Sheffield. … More

Neural magazine interview on live coding (2007)

Here’s an interview which appeared in the excellent Neural magazine in June 2007 (issue 27). A scan is also available. … More

PhD Thesis: Artist-Programmers and Programming Languages for the Arts

With some minor corrections done, my thesis is finally off to the printers. I’ve made a PDF available, and here’s … More