I publish this blog post with some nervousness, as I’m not a historian or musicologist. This is something I feel strongly about though, and as ever am very happy to receive feedback and corrections in the comments, either on this post, or on the fediverse.

Luigi Russolo was an Italian painter and composer who wrote the Art of Noises manifesto in 1913, which has become influential particularly in the academic, electroacoustic music genre. He gave the first concert of futurist music the following year, together with his collaborator and the founder of the futurist movement, Filippo Marinetti.

To understand the context of this work, we can read the Manifesto of Futurism, one of Marinetti’s manifestos published some years earlier, in 1909. The manifesto points are below, translated into English from the original French version by R.W. Flint. You could probably skip the first points and jump straight to point 9, which gets to the heart of the matter.

- We intend to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness.

- Courage, audacity, and revolt will be essential elements of our poetry.

- Up to now literature has exalted a pensive immobility, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt aggressive action, a feverish insomnia, the racer’s stride, the mortal leap, the punch and the slap.

- We affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath—a roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

- We want to hymn the man at the wheel, who hurls the lance of his spirit across the Earth, along the circle of its orbit.

- The poet must spend himself with ardor, splendor, and generosity, to swell the enthusiastic fervor of the primordial elements.

- Except in struggle, there is no more beauty. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece. Poetry must be conceived as a violent attack on unknown forces, to reduce and prostrate them before man.

- We stand on the last promontory of the centuries!… Why should we look back, when what we want is to break down the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed.

- We will glorify war—the world’s only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.

- We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice.

- We will sing of great crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot; we will sing of the multicolored, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modern capitals; we will sing of the vibrant nightly fervor of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric moons; greedy railway stations that devour smoke-plumed serpents; factories hung on clouds by the crooked lines of their smoke; bridges that stride the rivers like giant gymnasts, flashing in the sun with a glitter of knives; adventurous steamers that sniff the horizon; deep-chested locomotives whose wheels paw the tracks like the hooves of enormous steel horses bridled by tubing; and the sleek flight of planes whose propellers chatter in the wind like banners and seem to cheer like an enthusiastic crowd.

So, futurism, as expressed by its founder and Russolo’s close collaborator, was about violence, the glorification of war, destruction of museums, libraries, academies, and the fight against moralism, and feminism. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Benito Mussolini was a fan of Marinetti’s writing, and when Mussolini founded the fascist movement in 1919, Marinetti co-wrote the fascist manifesto.

So although the wider picture is of course complex, the history of Italian futurism can’t really be separated from the history of Italian fascism. There has however been some academic effort to do so, particularly with regard to Russolo’s image. The one book written on Russolo, by Luciano Chessa and published in 2012, briefly covers this whitewashing:

Russolo’s documented involvement with fascism has until now been erased from Russolo scholarship; his participation in the Duce-endorsed futurist exhibit at Turin’s Quadriennale in May 1927 has been thoroughly suppressed, as has his involvement with the exhibit at Milan’s Pesaro gallery in October 1929. His fascist connection is further covered up with the designation “antifascist,” which Giovanni Lista first applied to him in 1975. Lista supported this designation with a number of disputable post–World War II testimonies, and he claimed that in 1927 Russolo voluntarily went into exile in Paris to protest fascism.

Chessa, Luciano: Luigi Russolo, Futurist: Noise, Visual Arts, and the Occult. University of California Press, 2012.

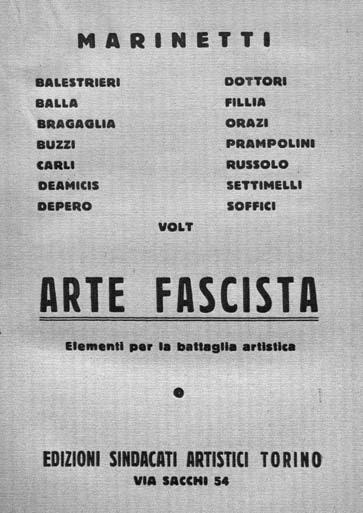

What led Russolo to Paris were professional opportunities, not politics. In fact, his permanent return to Italy in 1933, as well as some of his subsequent writings, signal first acceptance of and then allegiance to the fascist regime. Yet the fable of his antifascism runs through all Russolo scholarship—it is still maintained in Tagliapietra (2007) and Lista (2009)—with no convincing evidence to support it. In fact the opposite is true: for instance, on the title page of the publication Arte Fascista, published by the Sindacati Artistici Torino in December 1927, Russolo’s name is prominently displayed.

The Arte Fascista title page is shown in the image at the top of this post. It’s worth mentioning that Luciano Chessa himself is writing here to explain why Russolo’s life and interest in the occult isn’t much written about, the context of fascism being one of the reasons. Chessa points out that Russolo wrote his Art of Noises in 1913, whereas the fascist manifesto wasn’t written until 1919; on this basis, he argues that the former couldn’t have been touched by fascism. This argument doesn’t seem to add up when you consider that the futurist manifesto came first, was full of fascist sentiment, and was written by Russolo’s close collaborator in 1909. The Manifesto of Futurist Painters, co-written by Russolo the following year in 1910, was marked with similar calls for violence.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that Russolo and the wider futurist movement should be wiped from the history books, after all destroying libraries is what the futurist manifesto advocated. But I do feel that futurism should be explained in context. Russolo is frequently and uncritically referenced by academics and others simply as the founder of noise music. There is even an international prize for electroacoustic music named in his honour, the Prix Russolo. When I asked why the prize was named after a fascist, their facebook page maintainer simply said he wasn’t one, because Russolo (the prolific writer of manifestos) was simply a mystic who didn’t have any political thoughts.

Nodding towards the chip on my shoulder, I suppose music academics really love a dead white European or American male genius to associate themselves with, building an origin story for their music culture. In electroacoustic and computer music circles, the same half-dozen influences come up again and again. These male geniuses often do themselves cite diverse influences, from Ghanaian timelines to Indonesian Gamelan, but it’s their name that becomes associated with these influences, from a Western perspective synthesising vibrant, continually developing cultures into a fixed body of recorded or notated work, attributed to a single person. Our obsession with the creativity of singular authors rather than cultures of practice works not only to misappropriate, but also to limit creativity. Especially when an idea as rich and open to possibility as noise art gets associated with a singular, deeply problematic man like Russolo.

As an example, this breathless article claims that Russolo was the first person to make music from noise. This is clearly a ridiculous claim in denial of percussion, humans were making noise music by hitting things long before futurism or fascism came along. For example Al-Jazari made robots that would not only serve drinks and danced but “perform with a clamorous sound which is heard from afar”. He published his designs in his “Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices” in 1206, some 679 years before Russolo’s birth. Furthermore it didn’t take a singular genius to turn industrial noise into music; this seems to have been a universal human response, from the e.g. African and Italian diasporic music communities that founded house and techno in the USA, to the clog dancers responding to inhumane working conditions in cotton mills to create repetitive, and frankly astonishing noise music through dance that mimicked the machines (full performance here if you’re curious!).

So how to conclude.. I suppose I wonder that when people uncritically cite Russolo and Marinetti as influences, are they aware of the history? Indeed are they calling for the destruction of history, to make culture afresh? Is an unapologetically institutionalised practice such as electroacoustic music, really founded on the principles of a movement that calls for institutions, museums and libraries to be destroyed? I don’t think so, and perhaps twenty years ago, it was more understandable that people would cherry pick otherwise palatable ideas from fascists, while brushing the violence and destruction under the carpet. With far-right politics seemingly in the ascendancy in Europe and elsewhere, I think academics should be more careful, though. Either separate the ideas from the person, or carefully acknowledge the history in order to move away from it. But don’t award music prizes in the honour of fascists.

Update

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I received some pushback from this post, including in the comments below. In his talk “Russolo’s antifascism revisited“, Luciano Chesso (who is quoted above) goes into much more detail about Russolo’s close relationship with fascism. He clarifies many things, including the reason why Russolo didn’t participate in the founding of the fascist party (he was out of action with a fractured skull), why he spent so much time in Paris (he had a mistress there), that he nonetheless still performed in Italy and wrote for fascist newspapers during this time (so not at all in exile as often claimed), that when he returned to Italy in 1933 (which he would definitely not have done had he been an anti-fascist) he received a pension via Mussolini himself, and so on. The testimonials in support of him were all made post-war, by people who had their own links to fascism to obscure, and so were therefore unreliable. Personally I find his account much more convincing than that of Russolo’s supporters.

Second update

For a nuanced treatment of this topic, please see the section on Russolo and Fascism in this interview with Luciano Chessa conducted by Felipe Caramelos.

Amen Alex – thank you for this! I don’t think people even need to cite the Futurists as influence for us to need to be wary of their tropes. Elon Musk is case in point, of course, and on the cultural level as we’ve seen all too often in industrial music circles, for example, wherever there is love of extremity it can tip over into Fascistic urges. Even in scenes that are ostensibly egalitarian or inclusive, this can be true. The presence of what Kodwo Eshun brilliantly called “mechanismo” in e.g. techno and drum’n’bass bore amazing creative fruit, but when it has become the only game in town it tends to lead people to death of imagination and ever narrower creative dead end allies, and to the ugly attitudes that come with those things. NOT to say that extremity is bad or all extreme scenes are Fashy, not in the slightest, but we must be vigilant for the way it can create a conducive ‘mood music’ for Fascism, always.

Thanks Joe! Nice points including on Musk et al, Andreessen quoted the futurist manifesto in his godawful techno-optimist manifesto recently, although couldn’t bring himself to name it. If he senses the stigma, I’m not sure why some music academics don’t..

In music I think we still have a lot to thank the Rock against Racism movement for in keeping fascist musicians (like Bowie, at the time) afraid.

Hi Alex interesting article however I might have been victim of the white washing you mentioned about deleting reference to fascism and clearing up the image of Russolo, I am not entirely convinced. The Futurist advocated for the destruction of the establishment because they wanted to wake up the dormant minds through art innovation and new technology, the futurist where excited and inspired by the speed, the new sound of motors and the sound of the bombs, I dont think they meant going to war fo real, but staged theatrical play where they slapped the audience. They wanted to give rid of the indoctrinated, scholarly, dogmatic to make something new to advance civilisation and culture held back by scholasticism academic grounded on the classics holding back progress.

In this respect they where more near the super-humanism as ideology which also was associated wrongly with fascism, in fact fascism is quite the opposite, fascist did not like individualism and they defended the classical way of thinking, the woman must stay home to rise kids and the man should work with this hands and create prosperity as one unit as part of many, all contributing to the assigned task, fascist did not like individual initiative and they would suppress who wound not stand in line working for the common cause I mean this is the origin of the word fascism “il fascio”. I think the futurist just took an opportunity to put up a show “arte fascista” when at the time to be fascist was the norm and fascism was integrating all these ideas, I do not deny there is crossover between the two but in a distorted way. Say for example today, the equivalent of putting up a show at the Tate knowing the Tate history is into exploitation of slavery sugar trade and today sponsored by bp.

So sorry for the long message I am not used to writing much and not an academic at all I trying to brush off some dust in my memory, in any case I must say I feel myself a futurist at the root and super humanist as Nietzsche super-humanism and I can confirm that I am totally anti fascist, these ideas however looks similar from afar are not compatible as their nature is opposed, the fascist wants an homogeneous movement to work more efficiently and be stronger while futurist and super-humanist wants to free the intellect and praise the individuality and higher achievement of the individual so for how I see it they opposite, you seems to fall for the obvious and missing the point if I understood you right.

Hi Simone,

Thanks for the comment. Certainly not all futurists were fascists.

However Marinetti, the founder of Italian futurism certainly was fascist, as I point out above he co-wrote the fascist manifesto so it’s impossible to argue otherwise. There is no doubt the futurist manifesto prefixed and inspired fascism. In my mind, for all the reasons explained above, including from the only academic monograph on his work, there’s no doubt that Russolo was a fascist too.

I don’t think it’s possible to read “We will glorify war—the world’s only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman” or “We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice” as anti-fascism or feminism.

When fascists tell you who they are, believe them. I think you have indeed been misled.

Hi Alex, as I said I am not historian or researcher and my interest and knowledge in Russolo is limited and purely artistic and philosophical, the few readings I come across did not hint to fascism as far as I could understand, however I now see there are conflicting views, I not agree with your conclusion however similarity I did not with the associations of Nietzsche and fascism in the same way, I think fascist regime latched on these brilliant minds and ideas and profited, the situation has to be assessed in context, fascism was ubiquitous at the time and not considered something bad obviously people worked in this context without asking themself if they should fight it or living with it, by the same token my example about the Tate, for an artist accepting to present their work or a commission by the Tate means they pro colonialism? Or help whitewashing while profiting from the past? So in today climate do we have to label these artists as pro colonialist and pro imperialist and anti environmentalist due to the BP involvement? Or to aninvitation they will say NO I will not present there I am contrary to all that!

I think most of them will just go along and pocket the cash tell me if I am wrong so why in the past do you think was different? I think you can have it either one way or another not just where you want it to be

Having been awarded of the Prix Russolo by chance in 1992 and to be since 2010 the President of this contest, I was interested in the life of Luigi Russolo and often in friendly conversations I was opposed, a little summarily, to his possible political commitment to side of the fascists in Italy…I found nothing of the sort in my research and my intimate conviction and that Luigi Russolo was an artist, philosopher, musician and above all a mystic.

A few arguments can support my opinion:

1. Political engagement covers all actions taken by citizens to challenge those in power or participate in political life. However, we do not notice any of this in Luigi Russolo life, he did not join a political party or union, whether fascist or otherwise. He is not an activist, does not participate in strikes, demonstrations, signing political texts… He joins the futurist movement owing Boccioni in 1910 which is firstly artistic and thanks to which he will travel across Europe in painting exhibitions and then moved towards the sound revolution of the Art of noises with the construction of its noise makers.

2. Another proof of Luigi Russolo’s non-political interest are his writings whose subjects are artistic, musical, or mystical. I note and read:

– The Manifesto of the Art of Noises 1913 and new edition in 1916

When he returned to Italy in 1934 after a stay in Tarragona, he isolated himself with his wife Maria Zanavello in a villa in Cerro de Lavano where he wrote two spiritual books and led a painting creation workshop with friends:

– Beyond matter in 1938 (Al di là della materia)

– Dialogues between the self and the soul 1945 (Dialoghi Fra l’Io e l’Anima)

– The numerous correspondence that Luigi Russolo maintains with his wife and his friends has no political subject, Luigi Russolo’s interests lie elsewhere in metaphysics, Philosophy and Art. You can also read these letters which are kept at the Russolo Archives Museum of Trento and Rovereto.

There is not a single line of political commitment in these books and letters for the fascist movement created in 1919.

3. You wanted to quickly classify Luigi Russolo in the fascist category on the evidence of a document published in December 1927 in Turin, precisely the period when Luigi Russolo was in Paris and absent from Italy. I would thank you for publishing the complete document and giving more references (where, when, how, why…), your argument seems a little weak to me, but as you point out, you are not a historian, and I I noted well.

4. An artistic interest: Furthermore, I do not agree that Luigi Russolo was in Paris for purely professional reasons but rather for an artistic interest and a major fact, the Montparnasse district was a world cultural center at that time. Luigi Russolo arrives in Paris for performances of futurist ballets at the Théâtre de la Madeleine, works with Prampolini, participates in numerous painting exhibitions, presents his invention the Piano Rhurmorarmonium, plays it at the 1928 studio by adding sound to silent movies such as those of Eugène Deslaw, Jean Painlevé, Jean Epstein, and became the precursor of sound effects… He had one of his instruments destroyed by the League of Patriots (French fascist movement) during a screening of L’Age d’or, anti-clerical and anti-bourgeois film at Studio 28 in 1930. In Paris, he joined the artistic movement Cercle et Carré founded by Michel Seuphor and rubbed shoulders with Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian… He met the painter Fanny Hefter who was a Ukrainian with whom he will maintain an affair and who will make him met De Torre, a magnetizer, and with whom they will leave for Tarragona to deepen their research into Mediumship.

5. Testimonials

I urge and encourage you to read the Art of Noises, published in 1975 by Éditions de “l’âge d’homme”. You can find in this book the testimonies collected by Giovanni Lista: Nuccio Fiorda (Composer), Michel Seuphor (Writer, photographer, artist), Véra Idelson (friend of Fanny Hefter), Nino Frank (Writer who fled Italian fascism), Jean Painlevé ( French filmmaker and resistance fighter listed as a notorious anti-fascist).

You can also read the books of the historian Franco G. Maffina who wrote a complete bibliography on Luigi Russolo, or “The Artist Man” by Maria Zanovello.

I can nevertheless quote some extracts from these testimonies:

– from Véra Idelson: “I knew Russolo personally at the time of the futurist pantomime. He was a very intelligent man, with a subtle mind, Russolo was very anti-fascist – it could not be otherwise, given his great intellectuality and his high moral integrity…”.

– from Nino Frank: “Russolo had anti-fascist feelings, against the other futurists, almost all of whom had followed Marinetti by joining the party. I seem to remember that this opposition to fascism was one of the main reasons for his emigration to Paris. But it was, if I may say so, a purely sentimental anti-fascism, as one might expect from an idealist such as Russolo: he never got involved in direct action. And he did not often talk about the issue. Moreover, proof of Russolo’s anti-fascism is given by our friendship and the frequency with which we see each other: between 1928, when I cut ties with Italy, and 1933, when I go to get treatment in a sanatorium and therefore stop seeing Russolo, I am often attacked by the fascist press and most of my Italian friends forget my address… Now, this is precisely the period of great friendship with Russolo”.

In conclusion, I would ask you to complete your research with more in-depth elements than you did in your little article. It would even be appropriate for the sake of intellectual honesty that you add a question mark to your title as soon as possible.

I would be happy to help you in your process to find the truth an only the real story.

Hi Philippe,

Thanks for your response, I’ll answer briefly and directly:

Clearly Russolo undertook many political acts. In my blog post I quote Chessa, who has written the only monograph on his work. In this he dismisses the testimonials that you quote from Lista, on the basis of lack of evidence in support, and a wealth of evidence to the contrary, based on Russolo’s actions and writings. In these two paragraphs he argues that Russolo’s ties to fascism has undergone erasure, and I don’t see a reason to doubt him. His book can hardly be seen as a ‘hit piece’, this is an aside with the rest of the book about his artistic work and mysticism.

Indeed I am not a trained musicologist or historian, however your points respond to the quote from Chessa, and so your argument is with Chessa, and not me.

Luciano Chessa goes into great detail of futurism’s and Russolo’s relationship with fascism in this talk:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jb5sMEn7D2c

The reason he didn’t participate in 1919 was because he had a fractured skull. He signed all the manifestos up until then.

From around 42 minutes in he covers and debunks the post-war testimonies that you quote from Véra Idelson, Nina Frank and others, as being more about distancing themselves from fascism, and not being backed by any real evidence.

He then goes on to list his ongoing, documented involvement in writing for fascist newspapers, performing at fascist events in Italy, during the period that Lista claims he is ‘in exile’ in Paris! He was not absent from Italy as you claim, he kept his flat there where his wife stayed. In reality it turns out that he is only spending so much time in Paris because he is having an affair there, and doesn’t manage to bring her back to Italy only because she is Jewish.

I think you need to respond to Chessa’s research carefully, if you want your claims about Russolo to be taken seriously.

Gentile Mr McLean mi lasci dire che definire Russolo “fascista” è davvero una affermazione senza capo né coda. Portare poi a riprova il manifesto di una mostra di arte “fascista” (senza neanche precisarne la data) cui hanno partecipato più pittori ( anche molto importanti) delle più diverse estrazioni culturali è, mi scusi, un’operazione avventata. I capolavori della pittura russoliana presenti nei più prestigiosi musei del mondo sono degli anni 1911.12.13 Dopo queste date Russolo si è dedicato solo alla musica, alla filosofia e alle arti magnetiche. Con sporadici ritorni alla pittura che non era più quella futurista (e tanto meno fascista). E’ probabile che Russolo abbia concesso (magari controvoglia) dei quadri per quella mostra organizzata non si sa da chi. Ma comunque non esiste alcuna affermazione di Russolo in lode del regime fascista ed anzi, nel suo periodo parigino esistono lettere in cui lui descriveva tutto il suo fastidio per quanto stava accadendo in Patria. Mi consenta poi di meravigliarmi

di come un musicista come lei possa confondere i tam tam africani con gli intonarumori di Luigi Russolo. I primi attengono semplicemente alla categoria delle percussioni ( e in generale, se si vuole, tutta la musica viene fatta con dei rumori prodotti meccanicamente) mentre Russolo intendeva riprodurre artificialmente i rumori prodotti dalla civiltà industriale. Una bella differenza. Infine mi sorprende anche che lei affermi come l’unica biografia di Russolo sia quella del Chessa. Ce ne sono molte altre, molto più recenti e molto più aggiornate. Come già in modo molto puntuale le ha ricordato il signor Simone Longo le affermazioni del manifesto futurista vanno interpretate come una radicale e iperbolica volontà di rinnovamento, che sono andate ad infrangersi contro la tragedia della prima guerra mondiale. Ben prima che nascesse il Fascismo, che al contrario è animato da spirito reazionario e negatore della libertà dell’individuo. Grazie per la sua attenzione.

Dear Alessio,

Again, Russolo’s links to fascism are made clear in this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jb5sMEn7D2c

Russolo returned to Italy, wrote in fascist newspapers, exhibited and performed at fascist events, was given a pension by the fascist regime, and so on.

I’d be happy to hear about/read other monographs on Russolo though, please share references.

Noise in music, as far as music can be universally defined, existed across the world long before Russolo. Attributing such an idea to a single man does not make any sense to me.

Dear Alex, purtroppo nel ventennio 1922-1943 in Italia tutto era fascista. Si trattava di un totalitarismo. Non esisteva stampa di opposizione. Per cui tutti gli intellettuali e gli artisti se volevano esprimersi dovevano scrivere su giornali diretti da fascisti o partecipare a manifestazioni indette dai fascismi. Lei conosce il grande pittore comunista Renato Guttuso? Beh, partecipava ai concorsi del littorio. E un suo famoso quadro, “Crocefissione”, partecipò al premio Ferrara di Bottai. Quanto alla pensione come ferito di guerra gliela dava lo stato italiano, non il fascismo. Questa furia a caccia di fascisti o presunti tali mi pare qualcosa di imparentato alla famigerata Cancel culture. I miei rispetti. Alessio Alessandrini

Your argument on these points is better directed at Luciano Chessa, but clearly not everyone chose to stay silent and work for the fascist regime. Russolo chose to return to Italy. Chessa states that Russolo’s pension came via request to Marinetti.

Chessa also argues that it does not make sense to call Italian fascist prior to the founding of the Italian fascist party. This is a fair argument on the basis of semantics. But still, reading the futurist manifesto, it seems clear to me that it prefigures the fascist manifesto. I would certainly not want to associate myself with it.

I’m no fan of social media pile-ons, but ‘cancel culture’ is largely in the imagination of right wing fringe ‘culture wars’ zealots.

Buonasera Mr. McLean, ho scritto recentemente una biografa di Luigi Russolo.

Da tutte le ricerche che ho effettuato sulla sua vita e sui suoi molteplici interessi, mi sento di poter escludere nella maniera più assoluta un suo coinvolgimento al Fascismo, fermo restando che ogni manifestazione anche artistica durante il ventennio inevitabilmente era contraddistinta dall’etichetta fascista.

Non conosco la mostra di cui lei pubblica il manifesto, peraltro priva di ogni indicazione temporale. Posso dirle che nel 1927 un’unica opera di Luigi Russolo fu presentata nel corso di tre mostre. Si tratta di “Impressioni di bombardamento shrapnels e granate”, che reduce dalla Biennale di Venezia, terminata nel novembre del 1926, fu esposta alla Grande mostra di pittura futurista, Casa del Fascio di Bologna, 20 gennaio- 5 febbraio 1927, poi alla La Quadriennale / Esposizione nazionale di Belle Arti, Torino, 30 aprile – 15 luglio 1927 e infine alla Mostra di trentaquattro pittori futuristi, alla Galleria Pesaro di Milano, novembre – dicembre 1927.

Russolo in quel periodo era interessato unicamente alla musica tanto che solo a due anni di distanza, nell’ottobre del 1929, da Parigi scrisse alla moglie lamentando il fatto che era andato scomparso il quadro in questione e che non avrebbe mai più esposto assieme al gruppo futurista. E per sottolineare la sua distanza anche dai Futuristi aggiunge: “Le mostre futuriste servono solo a perdere quadri. Sono già due i quadri che ho perduto dato che anche questo non si trova! Ed è abbastanza!”

Fortunatamente la tela ricomparve nel 1931 all’Esposizione Sociale della Camerata Artisti Combattenti alla Permanente di Milano.

Del resto nell’ampia documentazione epistolare non fa mai riferimento esplicito al Fascismo; solo in una lettera alla moglie del 6 luglio 1927 da Parigi scrive: “l’idea di ritornare in Italia mi è veramente pesante e opprimente. Caro, amato, povero e schifoso paese! Vorrei piuttosto essere arabo o congolese che italiano”.

Penso di averle fornito qualche spunto di riflessione. La saluto Emanuela Ortis

Thanks for your your generous response Emanuela,

I think the date of the illustration is clear in my post – December 1927. It’s taken from Luciano Chessa’s book and described in the quote. I understand that Luciano Chessa has written further so far unpublished text on Russolo’s relationship with fascism, perhaps it will be included in a further edition.

Certainly your point that Russolo never refers to fascism gives me pause for thought. However a letter complaining about lost paintings, or about disliking Italy, isn’t convincing proof that Russolo didn’t hold fascist views. In any case, I’d be happy to receive recommendations for books and other references on the topic.

I’ sending the text of my answer again, hoping that this time an understandable translation will be made!

Buonasera Mr. Mc Lean,

ho scritto recentemente una biografa di Luigi Russolo.

Da tutte le ricerche che ho effettuato sulla sua vita e sui suoi molteplici interessi, mi sento di poter escludere nella maniera più assoluta un suo coinvolgimento al Fascismo, fermo restando che ogni manifestazione anche artistica durante il ventennio inevitabilmente era contraddistinta dall’etichetta fascista.

Non conosco la mostra di cui lei pubblica il manifesto, peraltro priva di ogni indicazione temporale. Posso dirle che nel 1927 un’unica opera di Luigi Russolo fu presentata nel corso di tre mostre. Si tratta di “Impressioni di bombardamento shrapnels e granate”, che reduce dalla Biennale di Venezia, terminata nel novembre del 1926, fu esposta alla Grande mostra di pittura futurista, Casa del Fascio di Bologna, 20 gennaio- 5 febbraio 1927, poi alla La Quadriennale / Esposizione nazionale di Belle Arti, Torino, 30 aprile – 15 luglio 1927 e infine alla Mostra di trentaquattro pittori futuristi, alla Galleria Pesaro di Milano, novembre – dicembre 1927.

Russolo in quel periodo era interessato unicamente alla musica tanto che solo a due anni di distanza, nell’ottobre del 1929 da Parigi scrisse alla moglie lamentando il fatto che era andato scomparso il quadro in questione e che non avrebbe mai più esposto assieme al gruppo futurista. E per sottolineare la sua distanza anche dai Futuristi aggiunge: “Le mostre futuriste servono solo a perdere quadri. Sono già due i quadri che ho perduto dato che anche questo non si trova! Ed è abbastanza!”

Fortunatamente la tela ricomparve nel 1931 all’Esposizione Sociale della Camerata Artisti Combattenti alla Permanente di Milano.

Del resto nell’ampia documentazione epistolare non fa mai riferimento esplicito al Fascismo; solo in una lettera alla moglie del 6 luglio 1927 da Parigi scrive: “l’idea di ritornare in Italia mi è veramente pesante e opprimente. Caro, amato, povero e schifoso paese! Vorrei piuttosto essere arabo o congolese che italiano”.

Penso di averle fornito qualche spunto di riflessione. La saluto Emanuela Ortis

Dear Emanuela,

I urge you to watch this very informative talk from Luciano Chessa:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jb5sMEn7D2c

He goes into great detail into how futurism prefigured fascism, the reasons why Russolo was absent from the founding of fascism (due to his fractured skull), the reason why he spent so much time in Paris (he had a mistress there for several years, perhaps that’s why he told his wife he did not like Italy), and the reasons why post-war accounts tried to erase Luciano’s links to fascism from the record. He did return to Italy to perform during this period, also while writing for fascist newpapers, and finally returned permanently with a pension via Mussolini.

As I said before, the source and date of the image is made very clear in my blog post.

@yaxuI'll read this with the care it deserves later but I do like the idea of those early / pre electric industrial musics.@poemproducer

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

@yaxu unfortunatly I can't share your message once again as it deserves,1 is the limit. Thanks for the update

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile